No chair is equally well suited for all body types. The perfect chair for a 6'2" computer programmer may be ineffective and even harmful if used for long periods by a 5'5" dentist. Your personal ergonomic chair should comfortably fit your unique body-type.

This guide highlights the fit you should look for when choosing your ergonomic chair.

- Body weight tolerance

- Seat height

- Seat depth

- Seat width

- Seat angle

- Seat cushion

- Backrest height and width

- Backrest support contour

- Backrest height adjustment

- Backrest pivot

- Seat-to-backrest angle

- Adjustment controls

- Armrest height

- Armrest length

- Distance between armrests

- Swivel

- Base

- Casters and glides

- Upholstery

1. Body Weight Tolerance

Chairs and portable supports should fit your body size and weight. Your weight can affect the adjustment capability, durability, and safety of a chair. Most office chairs accommodate up to 250 pounds of body weight and are not warranted for more. If you weigh more than that, ask us about special seating designed and warranted for heavier people.

2. Seat Height

The seat of a chair should support your thighs evenly while your feet or legs rest comfortably on the floor, footrest, or knee rest. On a traditional chair the seat's front edge height should match the length of your lower leg (popliteal height).

If you sit too low, your back will tend to flatten or round into kyphosis, making even a good backrest ineffective. In addition, you may feel pressure over your buttocks and tailbone. Taller people often find seats too low for comfort. If you are tall and don't have a tall enough chair available, raise your seat with folded towels or pillows, and don't forget to raise your work surface, too, in order to attain good seated posture.

If you sit too high, you will feel pressure behind your knees, and you may experience numbness or swelling in your feet. Shorter people often find seats too high for comfort. Shorter folks need to lower their chairs and work surfaces, or use a footstool at higher desks.

Footstools, however, may create other problems. We do not recommend footrests for seated tasks that require frequent movement between forward and upright postures, reaching, or scooting.

Remember, if you change the tilt of your seat you may need to readjust the height of your chair.

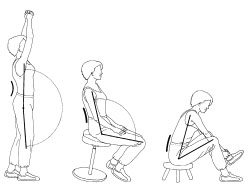

With kneeling chairs, there should be enough room between the seat and the knee rest, and the knee rest and the floor, to allow for easy access and movement.

3. Seat Depth

You should be able to sit in a chair without pressure against the back of your knees, with your back properly supported by the backrest, and with adequate buttock and thigh support. Allow a 1" to 3" space behind your knees to avoid pressure. Use a deeper seat for reclining, and a shallower seat for forward sitting, so you have room to tuck your legs under. Larger people prefer seats with larger surfaces for weight distribution.

4. Seat Width

Your seat should be wider than your hips, to allow space for movement and clothing. A seat 2" wider than you are is ideal. Remember that seat width can affect armrest width.

5. Seat Angle

Most people prefer a forward tilting seat for forward sitting, a nearly horizontal seat for upright sitting, and a backwards tilting seat for reclining.

A "free-float" seat tilt adjusts automatically with your shifting body weight, like a rocking chair. Some office chairs use an adjustable tension free-float seat to balance your body weight. However, most adjustable tilt tension mechanisms are too stiff for very light people, and too loose for heavier people.

The seat pan angle adjustment should not cause your torso-to-thigh angle to be less than 90°.

6. Seat Cushion

If you are looking for better weight distribution, select a seat with contour, extra padding, or with variable density upholstery materials. If you want a seat that is easier to move on, look for less contoured or firmer seats.

Keep in mind, the greater the contour, the less movement. While greater contour can be more comfortable, and can keep you from sliding in a forward tilting seat, it can also limit your movement.

A very contoured seat eliminates the sensation of sliding out of your seat during forward-reaching tasks.

7. Backrest height and width

All backrests should support your lumbar spine and allow clearance for your buttocks.

Your need for a backrest changes as your activity changes.

A narrow backrest frees your arms and shoulders for activity.

Low backrests (below the shoulder blades) and narrow backrests (no wider than the width of your waist) are best for tasks that require upper body mobility, so as not to interfere with your arm movement.

Tall backrests that support the shoulders are best for reclining. When you use a chair with a tall back rest, be sure that you still feel support in your low back area. A tall backrest that contacts your upper back with more pressure than it contacts your lower back, will cause your pelvis to roll backward and you will slump.

For reclining, your backrest should reach your upper back or neck, depending on how far you recline.

For upright sitting in a conventional chair, a backrest need only support your low back and perhaps your upper back. For upright sitting in a saddle-seat, no backrest is necessary.

For forward activity in a conventional chair, a support for the low back alone is sufficient, although some prefer no back support at all, or a torso support instead. For forward sitting in a saddle-seat, no backrest is necessary.

8. Backrest support contour

Match your neutral spinal contours to the backrest contour. The lumbar support should feel firm, without localized pressure points.

9. Backrest height adjustment

Backrest contours should match the placement of your spinal curves. Women sometimes need higher lumbar backrest placement and lower upper-back and neckrest placement than men. Women may also need a "buttock recess" between the backrest and the seat.

Backrests on most office chairs and some residential chairs adjust in height. Chairs without backrest height adjustment fit fewer people.

10. Backrest pivot

Backrests that pivot forward and back on a central axis permit greater movement within the low back and upper back, but can be uncomfortable if your spinal flexibility is limited. Many office chairs have a backrest pivot.

A backrest pivot sometimes provides a better fit for people with a larger than average thoracic kyphosis (a.k.a. forward head, upper back slump), or a larger than average lumber lordosis.

11. Seat-to-backrest angle

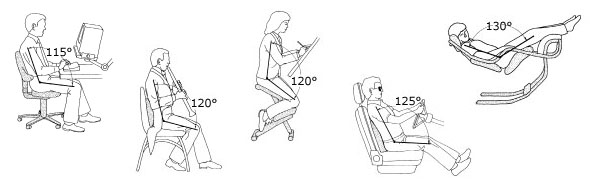

Your thigh-torso angle, and therefore, the seat-to-back angle in a chair, affects your spinal posture. In a chair, the tighter the seat-to-back angle, the flatter your lumbar spine will become, regardless of the agressiveness of the lumbar back support.

Your low-back curve deepens into an arch as your thigh-torso angle opens (for example, when you reach high overhead). Your low-back curve flattens into a forward bend as your thigh-torso angle closes (for example, when you sit on a low stool).

Some people do better with tighter seat-to-back angles (e.g., about 115°), and others do better with more open seat-to-back angles (e.g., 135°). If your body needs a more open thigh-torso angle than the chair allows, your buttocks and back will continuously slide away from the backrest leaving you with no lumbar support, and only your upper back resting against the backrest. If your body needs a tighter thigh-torso angle than the chair allows, you will find yourself sitting upright and not using the backrest, or tucking your feet under to try to stabilize your posture without a backrest.

Match your unique, neutral, thigh-torso posture to the chair's seat-to-backrest adjustment range. Some residential recliners and office chairs feature a "free-float" seat-to-backrest angle that automatically adapts to your changing postures with built-in spring tension.

Be sure to recheck your seat height if you make a change in your seat angle.

12. Adjustment controls

Adjustment controls should be within easy reach from a sitting position. This is especially important for seat and backrest tilt controls.

13. Armrest height

You should be able to comfortably support your forearms or elbows on the armrest without hunching up your shoulders (armrests too high), or leaning to the side to reach the armrest (armrests too wide) or slumping (armrests too low). Standard armrests should be at about the same height as the point of your bent elbows. Specialty armrests used for two-handed fine tasks (e.g., linear tracking arms, surgeon's arms, dental arms) are usually higher for use with the arms reaching forward.

There is a great deal of anatomical variation in individual arm lengths and body proportions. Some people need arm support only 4" above the seat, while others may need arm support 14" above the seat. No commercially available arm rests that we have seen, have adequate adjustment to fit everyone.

Arm support can reduce neck and back fatigue, facilitate body movements when you are seated, and ease back and leg loads when you enter and exit the chair. However, arm support is not always necessary or desirable. In fact, for some tasks, armrests can actually get in the way and cause problems. If you lean on your armrests too heavily you might strain your neck, wrist and hands when you type. In general, the better your pelvis is supported by the chair, the less you will feel the need for armrests.

Armrests are generally not necessary when you sit quite erect or leaning forward a bit, and your arms hang vertically at your sides (you'll need to bring your keyboard quite close to your body to type this way). The key here, is that your upper arms MUST BE VERTICAL. If you reach forward even the slightest bit, you will strain your shoulders and neck if you have no arm support. Armrests are rarely desired by people who saddle-sit.

Armrests are usually beneficial when you work in a reclined posture, and if you have to hold your upper arms forward of the vertical when you work.

14. Armrest length

The length of your armrest should allow you to sit close enough to your work to perform your tasks and still maintain contact with your backrest.

Armrests for reclined and non-desk activities should support your entire forearm, and if desired, all the way to your knuckles. For desk work, armrests should be recessed and provide support only to your forearm or elbow area to allow easy access to the work surface.

15. Distance between armrests

Correctly placed armrests can take stressful weight off your neck and back and help you get in and out of your chair.

Armrests that are too narrow interfere with arm movement; armrests that are too wide are not useful for rest or support and cause you to position your arms too far outward. People with narrow shoulders who use a wide seat may have to compromise, since seat width often affects armrest width.

The inside distance of the armrests should allow you to easily enter and exit your chair. Your hips should comfortably fit between your armrests. Armrests should never get in your way, or catch your clothing.

16. Swivel

Chairs that swivel let you change your reach and line of vision with less body twisting, but can feel unstable if you are doing precise work with your hands. For some, swiveling in a chair can be relaxing.

17. Base

Larger diameter bases provide greater stability. A large base is especially important on chairs that tilt very far back or sit at counter heights, i.e., drafting chairs. Swivel office chairs, except where noted, have a durable five-pointed-star, one-piece base.

18. Casters and glides

Carpet castors are standard on some chairs. They are especially useful for moving yourself toward and away from a table or desk. For use on a tile or wood floor, some chairs can be ordered with glides or with braking, locking, or soft friction castors.

19. Upholstery

Upholstery varies depending on the manufacturer. Most seats and backrests are made of high-density foam to give years of comfort under normal use. Most chairs are covered with durable fibers like nylon, olefin, wool, or blended fabrics. Note that many manufacturers exclude upholstery from their warranties.

Eileen Vollowitz PT